During the years of the World War, the cultural exile has led architects, artists and intellectuals to move away from their homeland, far from the anti-Semitic pressure. Alongside them, more unfortunate, long lists of lost identities. People who have been denied the right of their expression, removed from the professional registers and excluded without possibility of objection

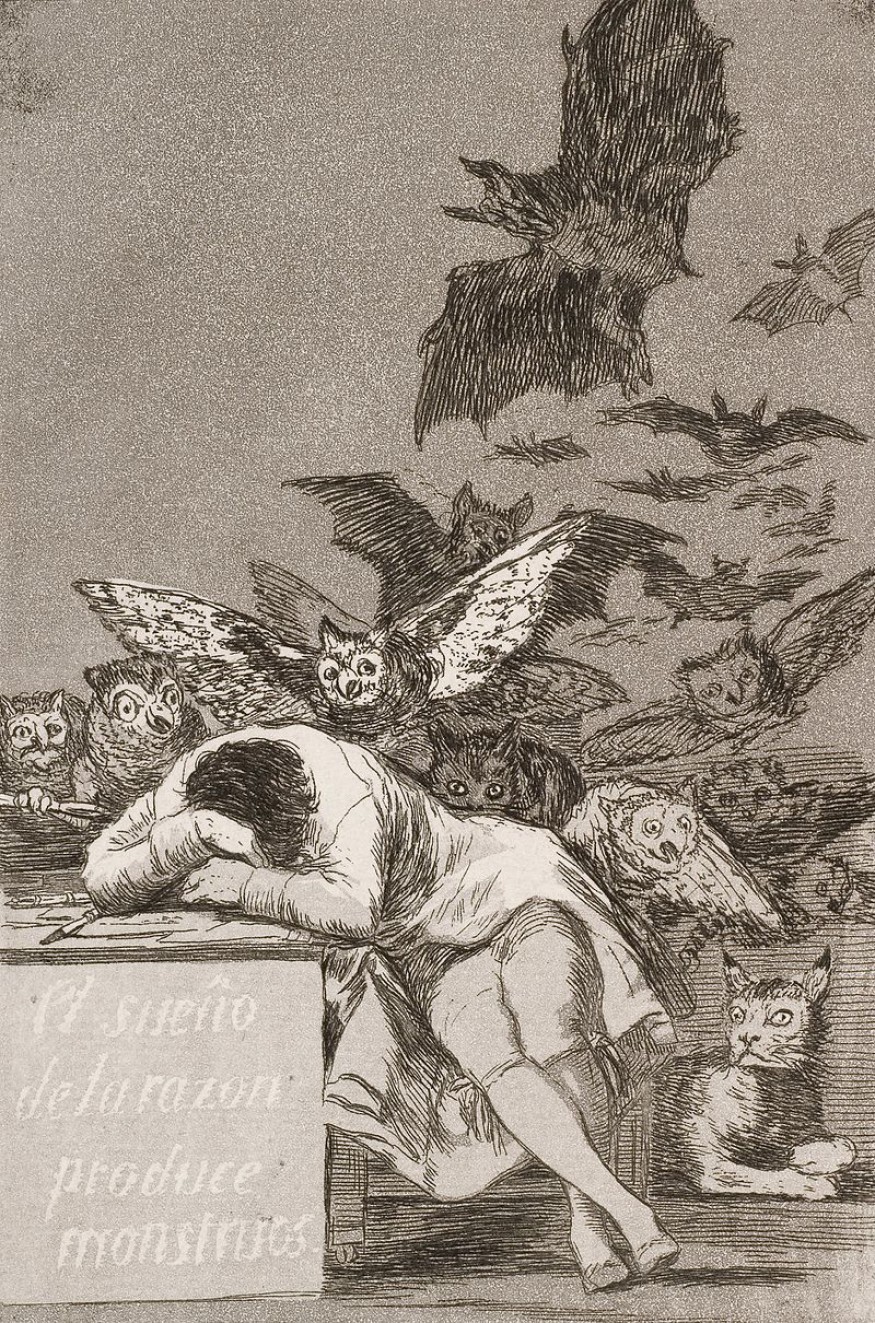

When in 1797 Francisco Goya created “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters”, he could not imagine that the Twentieth century would give rise to one of the most dramatic moments in the history of mankind.

Hate crimes, conflicts and racist manifestations were the wind of anticipation of the years just before the Second World War, when the fascist influence – and then the Nazi – was in the air. Discrimination and fear became the new sentiments that pushed society towards one of the most terrible moments of darkness.

“Personnes”, title of an artistic installation by Christian Boltanski – son of Jewish father –, plays on the ambiguity of the French term: to the singular it means “nobody”, to the plural “people.” Not directly linked to the Holocaust, the 2010 work for the Grand Palais in Paris presents itself as an incessant question about memory. Several elements evoke the Shoah, including the presence of clothes as “equivalent of the body”, image that refers to the undressing at the concentration camps, when, after crossing the threshold, thousands and thousands of people were forced to undress themselves of their identities.

“Personnes” by Christian Boltanski

“Personnes” by Christian BoltanskiRacial laws represent the sad apotheosis of a long process of changing the Italian and European law system, as well as the socio-cultural one. In Italy, on 29 June 1939 the elimination of Jews from professional registers was issued by requiring the total cessation of all occupational benefits (L. 29 June 1939-XVII, n. 1054, Discipline of the exercise of the professions by citizens of the Jewish race – OJ n. 179, 2 August 1939).

At the same time, a long and difficult migration starts to push away from their homeland several intellectuals among the European cultural landscape. However, the driving force of this process is not only rooted in anti-Semitism, but more widely in the oppression of any form of possible political and cultural threat. Alongside the others, long lists of architects begin to mark the exodus of a huge artistic exile.

Erich Mendelsohn, removed from the “German architects’ Union” and excluded from the Prussian Academy of Arts; Marcel Breuer, who left the Nazi Germany in ‘36 thanks to Gropius, who was already in the United States; Hilberseimer, reported by the Gestapo in 1933 together with Kandinsky and fled to America as many other members of the Bauhaus; Bruno Taut, moved to Japan and then Turkey; Belgiojoso, first supporter of international modernism, co-founder of BBPR and later deported to Mauthausen.

Architects and artists able to escape from a dramatic war. And, next to them, long lists of unknown names arrived to us without memory, in one voice. A garden of lost identities to which it has been forbidden to bloom. People whose right to profession, to expression has been denied. People who didn’t have the opportunity to express themselves through their work. People removed from their professional register, excluded and cancelled without any possibility of objection.

“The art of “building walls” retains a particular validity of human witness”, were Daniele Carabi’s words, Jewish architect deleted from the professional list “in defense of the Italian race” and forced to escape to Brazil. Yet, in the same years, walls and walls of brick were erected to build the concentration camps scattered throughout Europe. Those same walls, whose material is the expression of the continuous evolution of society, became silent enclosures of the industries of death.

“Muerte” is the fifteenth – and last – number of San Rocco magazine. Among the magazine’s contributions Irénée Scalbert recalls the image of Auschwitz and its architecture of extreme functionalism, using Pier Vittorio Aureli’s words: “The barest essential existence”. An architecture far from mankind, reduced to essentialism, to synthesis in form, as in process. To a nakedness which contains within itself the harshest sense of bewilderment, the idea of the human body as a mere set of organs capable of carrying out a task– just as the concentration camp is divided into parts, sections, each with its mechanical function to achieve a single (inhuman) objective. “But how bare must the barest be?” wonders Irénée Scalbert, “Auschwitz demonstrates that human life offers no objective basis upon which to establish such a minimum.”

An architecture so functional and inexpressive to be reduced to its own death, to be a mirror of a society with dying, empty values. Here are the famous words of Jewish German philosopher Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno: “After Auschwitz, no poetry, no art form, no creative affirmation is more possible”.

Yet, in May 1945, in Mauthausen, Belgiojoso wrote:

“I’m hungry, you don’t feed me,

I’m thirsty, you do not give me a drink,

I’m cold, you do not give me to dress,

I’m sleepy, you do not let me sleep!

I’m tired, you make me work

I’m exhausted, you make me drag

a dead companion for the feet,

with swollen ankles and his head

that jumps on the earth

with eyes wide open…

But I could think of a house

on the top of a cliff on the sea

proportioned like an ancient temple

I am happy: you won’t have me.”