Interview to Andrea Boschetti, founder of Studio Metrogramma: themes, projects, urban strategies and product design.

Can you tell our readers something about Metrogramma? How was your firm born? Which is its background and how is it today? Could you tell us more about your approach, the themes you dealt with and the issues you care the most about?

Metrogramma was born in the late 90s as a professional studio, and then in 1999-2000 it became officially an engineering company. Initially the partners were four, then two: myself and Alberto Francini, who in 2017 started a new individual path. Hence, I remained the founder of the studio from the beginning, together with three new partners: the basic idea is that Metrogramma continues as a team. Metrogramma is also to be understood as an ever-evolving architectural project, addressing the usual themes and challenges. Thus, at the basis of this continuous evolution there are cities and planning, architecture and design.

Magazines, journalists and specialized operators always ask us what we are specifically dealing with and I usually answer this question by talking about my educational background. I became an architect by attending the University Institute of Architecture of Venice (IUAV), with lecturers such as Bernardo Secchi, Gino Valle or Luciano Semerani, and historians of the caliber of Manfredo Tafuri or Massimo Cacciari.

It was a period characterized by a “Rogersian” kind of approach to training, “from the spoon to the city”, a very humanistic educational culture that ranged from the world of history to the world of design, from the city to the industrial product: this transversal nature is a trait that I kept.

I believe, in fact, that one of the characteristic features of Metrogramma is its attention to all the scales of the project. At the same time, the approach to the meaning that a project must bring with it in the realization phase is important for us, whether it is an architecture, a plan or an industrial product. This attitude may seem, in the age of specialization, quite anachronistic; however, I find that a multi-scalar and cross-cutting approach is necessary.

Metrogramma focuses on three words: grid, units and matrix. These themes acquire another meaning, in light of the "high" references mentioned above. Can you better contextualize these themes?

These concepts are the cornerstones of Metrogramma's design approach, through which we build the meaning of each job. The unit is the minimum element, nonetheless less complex, articulated or more banal than the others. The multiplicity of units builds an enlarged, a greater scale system, the grid. The matrix, on the other hand, is the systemization of all the heterogeneous elements of the project, and constitutes the complex system that is the contemporary city.

In fact, Metrogramma claims that each product of the design reflection is an attempt to better describe contemporary life, the era in which we live.

Speaking of contemporaneity: the choice to tackle different scales is also reflected in the decision of having outposts in the east and west of Milan, in very different geographies and contexts, in Moscow and New York. Is the reason behind that related to the work you have in progress, or is there something more?

Our offices abroad obviously were born from specific occasions. However, when you position yourself in a location that drastically differs from the ones in which you were trained, interesting job and research opportunities arise.

In particular, I personally followed the start of the studio in Moscow, where I lived for six years. I had a great passion and attraction for twentieth-century constructivist research and this moment was an opportunity to deepen that world and draw new ideas, new elements of analysis. In addition, Russia also gave me the opportunity to develop contemporary research.

TGP Milan 2030 Render

TGP Milan 2030 RenderI believe that the world, geographically speaking, is getting smaller and smaller: you move fast and get in touch with very different cultures with extreme ease. It is the approach with which this new accelerated speed is addressed that makes the difference, personally I am very receptive and, using the project as an exploration, I try to describe and better understand what I perceive. I am therefore not trying to impose a stylistic element, but to incorporate as many places as possible, inserting our sensibilities.

This does not mean camouflaging or being "conceptualists", but having respect for places without giving up expressing a radical statement, albeit with the ways and times that that context requires. That is what it is about: a listening-proposal: starting from listening to what one sees and interprets; the choice is not to blend in but to propose something.

In the last twenty years we have witnessed, if we want to say, an arrogance of international architecture through the so called “archistars”. When I speak of the need to "learn how to listen to places" I do so in the most modernist assumption. If we think of the travels of Le Corbusier or of the other great masters, who were fascinated by places far from their formation: it is not always necessary to impose a stylistic feature to measure oneself with a place, because often places give answers that every professional, through his/her personality and his/her research goal, can then put together and rework.

In the historical moment we are living in today, this arrogance is gradually disappearing: architecture is now increasingly creeping into places to solve problems and build new proposals, also opening to bets that are not necessarily in line with the language that is convenient for the market.

Milan and the Territory Government Plan: Metrogramma participated, working on the 2007-2008 TGP, triggering an initial research which then led to the approval of the new Plan a few months ago. Thus, was there also in this case, a process of study-analysis-listening starting from the "pre-existence" and the desire to propose, starting from this, a series of projects, dynamics and strategies?

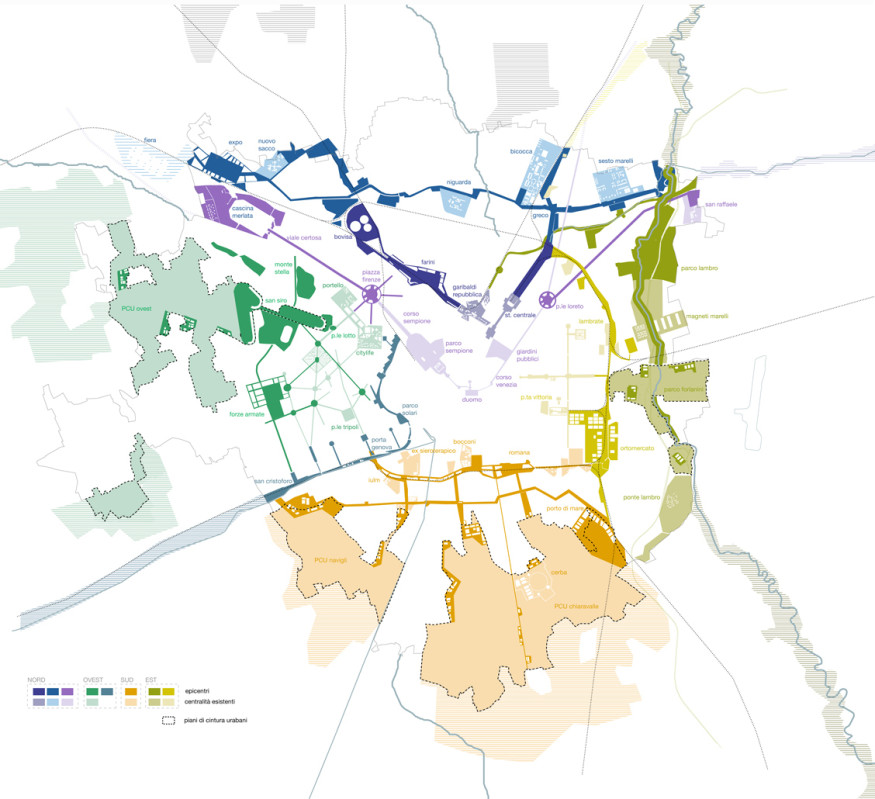

Map of TGP Milan 2030 - courtesy of Metrogramma

Map of TGP Milan 2030 - courtesy of MetrogrammaA small premise: the TGP was born from a research work on the city that I cured previously with some great masters. In fact, I worked for many years near Bernardo Secchi, a person who knew how to listen and interpret the complexity of the contemporary city, a figure who attempted a revolution and a strong reform in urban planning.

The Plan of the Government of the Territory of Milan that I worked on in 2006-2007 was a great laboratory, where I managed to put together an extraordinary team of young people with whom we revolutionized the way we do urban planning in cities. The TGP was no longer a design dropped from above or a formal vision accompanied by a plan of rules to be implemented, but a strategy capable of incorporating the changes of the contemporary city which, discretionarily, allows to make appropriate choices in the interest, above all, of the public.

This modus operandi was also favored by the regional law for the government of the Lombard region published in 2005. Our vision worked with themes related to listening and to the description of the problems: themes that are extremely essential when dealing with a strategy for a contemporary city. The Milan TGP was also a model for Europe, in fact I long discussed this with colleagues such as Richard Rogers, who at the time was leading a team for the new London plan.

The plan was based on widespread urban regeneration policy ...

The urban regeneration approach that was widely used at that time was not yet current. In fact, we decided not to think in terms of a city in continuous expansion, with new suburbs, but to work within it and in particular on three major themes: first of all, the recovery of large disused areas and the reconnection of the city with the places that at that stage were unknown to the public because they were not intended for the public use such as train depots - nowadays central to the Milan urban debate - or the large abandoned industrial areas.

The second element was the attempt to convey by means of simple rules the burdens derived from these major transformations towards the public city, that is, towards the transformation of the streets and squares, in order to insert a new quality of the city even among the built. The third major element was the recovery of existing buildings, historical but especially in the suburbs, which needed very precise rules to be put back on the market, recovered, transformed and redeveloped.

Compared to Gregotti and Cagnardi’s 1995 Turin PRG (“Piano Regolatore Generale” – or Master Plan) at the end of the 90s which represented an innovation of tools and strategies, Milan’s TGP (started in 2007-08 and then ended in 2019) instead certainly proposes an advancement of thought and strategies. If in Turin there was talk of a regeneration of abandoned industrial spaces, especially through a residential SLP, in Milan the effort was to engage different functions, working on the public city and recovering historic buildings…

Milan, like Turin at the time, manages to interpret current demands, the changes that are taking place within the city, such as the structure of the demographic population or mobility. Without taking anything away from the Cagnardi’s Plan - which I know well, because in those years I was teaching at the Politecnico of Turin - the Milan TGP is certainly very different.

The great matter of the functional mix and the urban strategy without having a city divided into homogeneous areas or with intended use changes the cards on the table in a radical way: it is a plan in line with the needs of the contemporary world. With satisfaction, Sala’s administration with Pierfrancesco Maran has continued this work, improving it, so today the market and developers have tools to be able to recover buildings for previously unforeseen uses, such as cohousing, coworking, hospitality or assisted housing.

These are all elements that keep the interest of operators and investments high, and therefore they don’t "kill" the city. The public city must lead by example and solve problems, but resources must come from private individuals: combining public and private is therefore not an essential but vital requirement.

We talked earlier about the needs of the city and the responses of the city design, we would now like to take a step up to tell another project, that of Scalo Milano City Style, with which Metrogramma also won the Retail The Plan Award

Scalo Milano City Style, Milan, Italy

Scalo Milano City Style, Milan, ItalyThe assignment, won on private competition, was unexpected and represented a new challenge for Metrogramma: usually, we don't deal with shopping centers. What I think rewarded us was the interest and the shift in investments made between the part of the volumes and the collective spaces, where events and demonstrations, concerts and activities for families and children regularly take place.

I grew up by working together with Rem Koolhaas, so I have a deep passion for architectural themes, however I want to underline in particular an effort that has been made on this project: the great ambition to connect Scalo Milano with public transport. Very few people remember it, but in my opinion, it is one of those strategic choices that does not make these places islands lost in the desert. In fact, today different models operate compared to the classic shopping center, where other functions are linked to retail. In this case, it was a question of reviving a portion of the city, with schools, a public space and a whole other series of services.

Often shopping centers are places that reproduce real cities, meaning they are fake places. One of the things Metrogramma wanted to avoid, in this perspective, was to rebuild a faux city. Almost all shopping centers in the form of cities have a post-modern nature and recreate a fake historical city; we wanted to work on the contemporary and its details, with mirrored, reflective, colored facades. It is a city model that did not yet exist: on the one side the public city, the element that should raise interests and must be a continuity; on the other, the radical nature of a kaleidoscope of colors and reflections that somehow make fun of brand communication.

Can you already give us any sneak preview on current projects or interesting work in progress?

In addition to Italian projects, we have some international works currently handled by our offices.

Since I am also the art director and head of design of the contracting side of Luxury Living Engineering that makes luxury supplies, I am working together with Metrogramma on a very elegant project in the heart of Budapest, which is a mixed-use building of over 28,000 square meters which will have residences, offices and a ground square with services, which will be called Szervita Square. It is a "building furnished by Bentley home": a Bentley Home branded building, which recreates a condition of absolute quality in the heart of Budapest, enhancing an entire portion of the city.

Metrogramma is also one of the studios who has been invited to work on Neom City, a new and experimental city in Saudi Arabia where we are working on the masterplan for some villas on the sea. It is a sort of new town, a great bet set on the involvement of the greatest researchers in housing and urban planning, where the aim is to imagine the city of the future, sustainable and zero-impact. If and when it will be implemented is a matter of geopolitics: it is, in any case, a great opportunity to do operational research.

We are also dealing with some penthouses in some new Miami skyscrapers, and not to forget our traditional leap in scale, we are also working on the design of products for many companies, including the same Luxury Living for Bugatti and Bentley products. Even if time is always short…